- ImpactWe help parliaments to become greener and to implement the Paris agreement.We support democracy by strengthening parliamentsWe work to increase women’s representation in parliament and empower women MPs.We defend the human rights of parliamentarians and help them uphold the rights of all.We help parliaments fight terrorism, cyber warfare and the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction.We encourage youth participation in parliaments and empower young MPs.We support parliaments in implementing the SDGs with a particular focus on health and climate change.

- ParliamentsNearly every country in the world has some form of parliament. Parliamentary systems fall into two categories: bicameral and unicameral. Out of 190 national parliaments in the world, 78 are bicameral (156 chambers) and 112 are unicameral, making a total of 268 chambers of parliament with some 44,000 members of parliament. IPU membership is made up of 180 national parliaments

Find a national parliament

We help strengthen parliaments to make them more representative and effective. - EventsForumNY, United StatesThe Parliamentary Forum at the HLPF is designed to engage parliamentarians in assessing progress toward the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) at the global level.

- Knowledge

Discover the IPU's resources

Our library of essential resources for parliamentsGlobal data for and about national parliamentsLatest data and reports about women in parliamentResolutions, declarations and outcomes adopted by IPU MembersRecent innovations in the way parliaments workThe latest climate change legislation from the London School of Economics' databaseIPU on air- Conversations about parliamentary action

The UK Parliament holds its first virtual Prime Minister's Questions and Ministerial Statements on the coronavirus. ©UK Parliament

The COVID-19 pandemic has created challenges for every one of us. Parliaments are no exception; they have suddenly found themselves unable to operate as before and, when this happens, it can challenge the very fabric of our democracies.

Our systems of parliamentary democracy are well suited to addressing a crisis of the magnitude and complexity of COVID-19 but many parliaments have struggled to function during the pandemic. Enforced remote working and social distancing has led to a reduction in (and in some cases, suspension of) sittings. Parliaments are there to scrutinize what the government is doing and to pass new laws, both vital at this time. When they cannot sit, they cannot do this. For some parliaments, this has led to a rapid and dynamic cycle of enforced innovation, producing our first virtual and hybrid parliaments. Digital technologies have been embraced as a solution to remote working and the remote sitting of parliaments the legacy of which will last long after the pandemic has subsided.

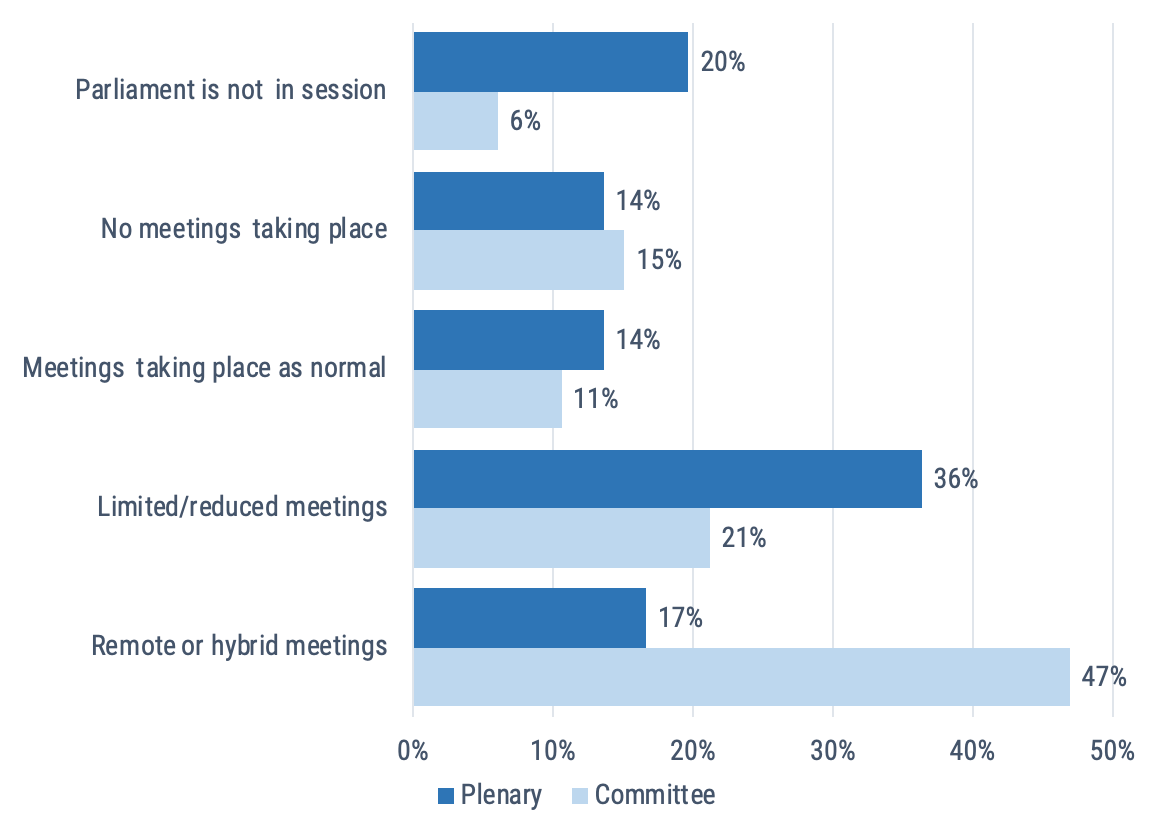

The IPU’s own survey of parliaments during the pandemic has shown that, by June 2020, 14 per cent of parliaments were not sitting and 36 per cent were holding reduced meetings. In contrast, 14 per cent of parliaments were meeting normally and 17 per cent were operating in a form of virtual or hybrid mode.

It is too early for us to fully understand the future benefits and the full extent of the limitations for virtual parliaments. Concern has been voiced that the virtual setting will dilute the effectiveness of debate and remove spontaneity in the plenary setting, but equally that it has proved beneficial for members in geographically more remote locations. Whatever happens, the COVID-19 Pandemic has created an opportunity to accelerate parliamentary innovation and to develop new working methods that could have a significant impact on the way parliaments look in the future.

We have highlighted four key areas for parliaments moving to a remote or hybrid model: reviewing and amending regulations and procedures; considerations for remote working and attendance; the conditions to support effective remote participation for members; and finally, considerations and issues relating to the underlying digital technologies.

Procedure

Before parliaments can operate in a remote or hybrid manner, they must identify the legal and procedural barriers to doing so. It has proven to be the case that many parliamentary systems have been legally or procedurally defined in such a way that it is either explicit or implicit that they must meet “in personˮ and that decisions are ratified by a vote of those members “presentˮ. Many parliaments have reviewed their legislative framework and brought forward amendments. Brazil, Finland, Latvia, South Africa, and Spain are such examples. The New Zealand House of Representatives and UK House of Commons have formally amended parliamentary standing orders to allow for remote sittings.

Availability of staff and members

Broader public health regulations relating to the pandemic, as well as social distancing rules within parliaments, are likely to affect the availability of staff. Many parliaments report that staff are working remotely wherever possible and only skeleton staff are allowed to work within the parliamentary estate. The European Parliament expects its IT team to be working remotely until at least September.

Remote working requires secure access to the systems used in parliament, and it is clear that parliaments that have invested in remote access and cloud-based solutions prior to the pandemic are at an advantage here. The Parliament of the Maldives is an excellent example of how prior investment in strategic planning and IT has made it easier for them to respond to current circumstances.

Working modalities

When a parliament operates virtually, not only the formal procedure but also the practical process changes. Members need to have access to a sufficiently reliable and high-speed internet connection, which can be difficult in remote or rural areas. Angola has used regional public buildings where an MP can attend if their home-based connection is not sufficient. It needs to be appreciated that this is a new way of working for many, so training is required to support members and staff. In the UK, MPs have been given guidance on a suitable space and configuration, including lighting and backgrounds. Voting is one of the more challenging areas for the remote or hybrid plenary but parliaments must also consider the timely distribution of documents, the handling of amendments, the management of the official record, and how to ensure that openness and transparency are not adversely affected.

Technology

There are two clear favourites in terms of video conferencing; Zoom and Microsoft Teams are the solutions chosen by most parliaments for plenaries, committees and internal meetings. Other options include Cisco WebEx, Google, Jitsi and Kudo (which is particularly suited to multi-lingual parliaments).

All of these tools present some level of security risk and it is therefore important to consider how they are to be implemented: whether they should be hosted in the public cloud (lower cost) or as a private installation (higher cost), and how access will be provided to participants (limited to specific email domains, etc.). The licensing costs and technical support requirements – particularly when there is a large number of users – are important considerations. A further issue is understanding how a videoconferencing tool will integrate with legacy broadcasting systems.

Evidence to-date suggests that the greatest point of weakness in videoconferencing security lies with end-users accidentally sharing meeting and password details via social media. Other concerns raised by parliaments include the legal jurisdiction in which data is stored (even temporarily) for these applications and how this is affected by data protection laws.

Debates are only one of the requirements that technology must support; members must also be able to receive papers in a timely way and they must be able to vote. Voting is perhaps the most challenging process to operate remotely. Some parliaments, including Brazil, Spain, the UK and Zambia, have developed internal applications for members that include a voting function. Latvia has recently implemented a secure e-Parliament system that allows it to operate in a completely virtual manner. Smaller parliaments are relying on the voting and polling options within videoconferencing products.

Emerging evidence from parliaments suggests that, where it is possible, separating the videoconferencing platform from the technology used for voting is good practice. This allows the videoconferencing tool to be changed more easily.

CIP’s contribution

The IPU Centre for Innovation in Parliament has been taking a strong lead throughout the pandemic, helping parliaments around the world to adapt to this new and challenging situation.

- We have co-ordinated responses from parliaments and shared these widely, presenting our knowledge in webinars from Ukraine and the Western Balkans to Latin America, regular publishing in blogs and articles, and helping the mainstream media around the world to understand the implications of the pandemic for parliaments and the solutions being implemented.

- Through our regional hubs, we have held virtual meetings for parliaments in Southern Africa and Latin America to share good practices, discuss innovation and identify solutions.

- Our online groups have provided a vital connection for over 50 parliaments to share ideas, discuss solutions and collaborate.